Water is life. Just ask Egypt

Wading into the corn fields at the desert’s edge, machete in hand.

As Ramadan and September ended, we moved camp again. We were no longer deep in the desert but were now located a short walk across the desert sand from the agricultural lands we were going to work in next.

The desert area around our new campsite also contained a couple of much smaller step pyramids and a gleaming, five-foot stainless steel pipe sticking out of the sand where I was told our client, the Brazilian oil company, had found some natural gas.

It always amazed me how abrupt the transition was from lush greenery to dry, lifeless desert. It was not a soft, wavy line in the sand. It was a hard line drawn by a fine-point pen. Just an inch away from plump green plants, the absolute dryness in the desert sand meant not even the tiniest weed could grow.

Egypt is a green ribbon alongside the mighty Nile River and Delta

96 Million Egyptians live on 3% of Egypt’s land

Most of us have no idea that Egypt considers itself a farming nation. However, a country once considered the Breadbasket of Rome went from exporting 26 million metric tons of wheat to now needing to import 40% of its food.

Driving to the area we would survey each morning, we would drive by men with long beards, turning Water Screws, used since 300 BC, to lift irrigation water into their fields.

The level of poverty we would see every day in our work in the agricultural areas was ghastly. In all my travels, hitchhiking and public transport, overland from Egypt to Cornwall, England, and back, all the way through Europe, Greece, Turkey, Iran, dirt-poor Afghanistan, Pakistan, and even in the slums of India, I never again saw such dismal poverty.

Warning: Shocking Graphic Description ahead:

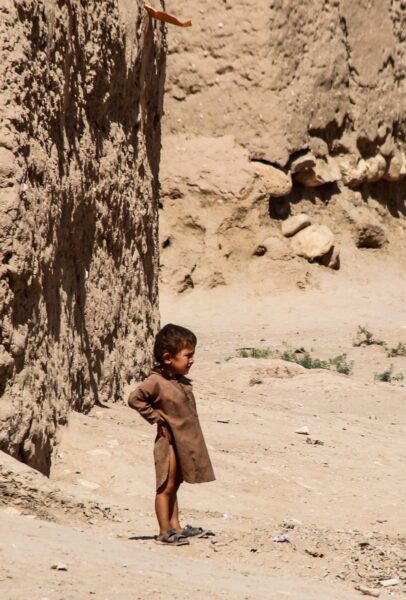

The picture I can see to this day is mainly of the little children wearing nothing more than rags. I could not tell if the scraps of cloth had ever been actual clothes. They looked like the grime-covered, torn-up rags sitting in the rubbish bin outside a car mechanics shop. This is no exaggeration.

The picture I can see to this day is mainly of the little children wearing nothing more than rags. I could not tell if the scraps of cloth had ever been actual clothes. They looked like the grime-covered, torn-up rags sitting in the rubbish bin outside a car mechanics shop. This is no exaggeration.

There were always at least 20 kids just standing around as we drove by or set up our instruments for our work. Each one of the kids had a dozen flies just sitting around their eyes as they quietly stared at us. They no longer even bothered to swat at them.

What must have been their dwelling structure, since there was no way it could be called a house, was just a plain, hand-made mud structure, maybe 8 to 10 feet tall, with empty openings for windows and doors. My guess was that there was probably nothing much inside these structures. Perhaps some tools to prepare food with? An ancient inherited blanket?

I have always felt gratefully fortunate since seeing this extreme poverty.

The farmers, most likely the parents of some of the kids, were friendly and hospitable. When our crew went hacking through their ripe sweet corn fields, they generously offered all of us some ears to eat on the spot.

It was, by far, the juiciest corn I have ever eaten. Even uncooked, right off the stalk, it was soft, creamy, super juicy, and delicious! The Egyptian on our survey crew, who was a trained surveyor and did all the communicating in Arabic with the farmers also had sweet corn juice trickling down his chin.

Off to the side of the field was a large, overweight man, the kind of guy who looks like organized crime in any country you visit. I was told by my Egyptian crew member he was a retired general in the army and was our liaison with the poor farmers, making sure they did as they were told. To this day, the Army has huge business holdings in Egypt.

Our new camp’s next-door neighbor – an ancient step pyramid

Our new neighbor, for a month or two, was a small, insignificant step pyramid, the kind you will see here and there. There are even a few near the major pyramids at Giza. Tourists ignore them.

Our new neighbor, for a month or two, was a small, insignificant step pyramid, the kind you will see here and there. There are even a few near the major pyramids at Giza. Tourists ignore them.

The pyramid in our neighborhood, though small compared to the giants at Giza, still had some things of value. Or at least that’s what one of our laborers told me one day, one of the guys who would work the chain.

“Sahib, I take things from this place long time ago.” I must have looked incredulous, imagining death by firing squad or something if he was caught stealing.

“Needed money to get wife.” Ahhh … I immediately understood and smiled. A simple man, trying to live his best life with not a penny to his name. And, of course, he wanted a wife and a family, like most people anywhere.

“I am happy you found a wife, Sayed. You work hard. I wish you a good life,” was about all I could think to say to him. I wanted to shout at him, don’t tell anyone else about that, but, what did I know? Not Much!

When you gotta go, desert-style

One day, I was driving with the camp Party Chief, heading back to camp from Cairo after my seven days off from work. I realized that I had to go, and not the easy, number one. I needed to do some serious bathroom business, and we were 20 miles from nowhere.

My boss pointed at the glove box in our gray Chevy truck. “There’s a roll of toilet paper in there,” he said as he slowed down and pulled over to the edge of the invisible sand road we were on. There was a berm of hard sand, and then, about twenty feet further away, a dozen men were hanging out, squatting by the road, taking a break perhaps.

They were taking a break from some farm work they had been doing. All of them wore the usual kaftan with a long cloth wrapped around their heads.

They stared at me from the moment I got out of the truck, pulled down my pants, deposited a respectable pyramid of my own, pulled my pants back up, and got back into the truck. No one blinked an eye or made a peep. I learned that day just how raw life in the Egyptian countryside can be.

It obviously was no big deal. My boss didn’t say a word. It was like I had gotten out to re-tie my shoelace.

The head surveyor goes on Christmas break – I’m on my own!

As our surveying moved deeper into the denser populated ag areas, there were more roads and more obstacles. That was when the head surveyor, the one who actually knew what he was doing, left for a few weeks for his annual break.

I was in charge! I was on my own! YIKES!!! Lucky for me, our Egyptian crew was top-notch. The Egyptian on the crew who knew surveying was super helpful and a tremendous support. And, since we were in a known area, there was no need to do super complex calculations and celestial observations to get our lines located on the maps.

But it was no longer flat, and it was hard to know where to pound in the stakes. We had to be much more careful with our elevation measurements, using the tall survey rod like a huge, vertical tape measure.

“You think we’re gonna let a million dollars of equipment wait on YOU?”

It was a tough day. I was in over my head, trying to figure out how to proceed surveying up a fairly busy road, so I paused for about half an hour. I quickly found out this was a mistake.

One of our company trucks comes zooming up, and a short, irritating guy from the Cairo office jumps out and starts yelling at me. “What the F___ do you think you’re doing!?! Get this F___n crew moving! We got the buggies and recording truck 20 minutes away!”

And then the line I will always remember, “We’re not gonna let a million dollars of equipment wait on you!”

So, I knew enough to at least make it look like we were making progress. We continued on for another few hours and got a good distance ahead of the seismic recording crew. Was our survey accurate? Time will tell.

When I got back into the office that day and began crunching the numbers of the angles and elevations in our field notes, I realized with a deep sense of dread that the numbers didn’t balance.

I mimicked the missing head surveyor – “FAAAACKKKKKK,” I said to myself. Do I really have to go back out there and survey this place again, I asked myself, feeling stomach acid rising in my throat.

Guardian Angel to the rescue!

It dawned on me suddenly that I just needed to spread the error across ALL the numbers so that, in the end, they balanced. The finesse method. Like balancing a financial statement when you just can’t find the missing $0.05. Just throw in a made-up number and call it good.

Then I finally smiled as I thought, “No sir! We are not gonna let a million dollars of trucks and buggies wait on the wrong numbers, we’re gonna make up the numbers so everybody is happy!

Saved by the Christmas Break

Fortunately, we only had a couple more weeks until the whole camp shut down for the Christmas holiday.

Once I found out that the company left one ex-pat behind to man the fort and monitor the camp, I volunteered. I certainly couldn’t afford to fly back to Dallas. I knew my mom would love to see me, but I just couldn’t let myself spend all my hard-earned money going back to a place that I could not wait to get out of.

There was almost nothing I had to do during that time except call into the Cairo office everyday via radio, and be around at certain times in case they called. I had free range of the galley, cooking and eating what I wanted, and got to sleep in the crew boss’s private room which was deluxe compared to our sleeping digs.

I envisioned some peaceful time, reading and playing my guitar. The crew boss gave me a few chores. Have so-and-so pick up these five mattresses and take them for an exchange, little things like that.

I had the peaceful break I imagined. One evening, I made some sort of great dish or baked thing, and I thought I would go out to the Egyptian tent and share it. I called out, and someone opened a big flap of door. As I was offering my dish, I glanced inside the tent. Bad idea!

I have no idea what the guys were doing, but the way they jumped up and started to pretend they weren’t doing anything, I immediately recognized I had interrupted something… perhaps a little kinky. My timing was terrible. I backed away from the door flap, handed over the dish, and never went to the Egyptian tent again!

Corporate Survival Rule #1 – Always have someone else to blame!

When the crew came rolling back into camp around the end of the first week of January, the Italians all had big smiles on their faces, the Canadian was grumpy and sullen as ever, and my crew boss started acting weird.

Something was up, but I was too inexperienced to realize someone had screwed up and a scapegoat would have to be sacrificed in the name of keeping one’s job.

A couple of days later, there was a meeting in the office trailer with the actual regional boss from Cairo. I was invited. Gulp.

Apparently, one of the Egyptians had taken the truck, as the crew boss had told me he would, and done something that the higher-ups did not like. Eventually, I heard the crew boss say, “I don’t know why Peter told him to take the truck,” talking to the regional boss.

“Well…” I thought to myself, “Perhaps because you TOLD me to have him take the truck…” and realized that this was The Blame Game. One of my colleagues in camp had explained to me a few months prior that the first rule in corporate life is to always have someone else to blame for your screw-ups.

Then, the attention turned to me. “All Peter seems to want to do is travel on his breaks. He doesn’t seem to be serious about doing the work.” Or some nonsense like that.

Time for another pivot!

So, I kept calm, to the best of my ability, and explained to these guys who were somehow worried about their jobs that I was told to take the truck, and there had never been any complaints about my work, so why was there a problem with what I did on my breaks?

I knew by the end of the meeting that my time in Egypt was up. But I did not say a word about quitting. I waited until the time was right, my plans were made, and gave my notice.

A week later, a secret informant showed up from the HQ in Houston, masquerading as the New Surveyor to replace me.

Apparently, he had been sent by the corporate big shots in Houston to find out why our crew kept hemorrhaging surveyors!

Boy, was I happy to talk!